3.

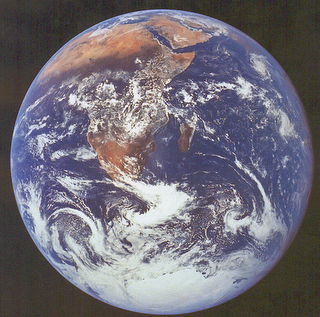

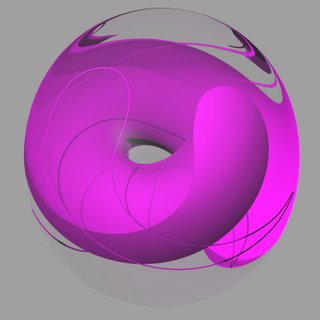

I’ve called this story “Time Particles”. I don’t know what it means. I thought of it the other day, while I was lying in bed in a half-awake-dream state, musing about Fred and his story. The phrase “Time Particles” just popped into my head. What would the world be like, I thought, if time has substance and is made of particles?

In my semi-conscious state it kind of made sense. I could see all these time particles swirling about in the chaos of reality like alphabetti spaghetti in a tin of Heinz soup.

I’d seen the cover of the New Scientist magazine earlier in the week, and the caption read “You Are Made of Space-Time”. I liked that title. I like the idea that I’m made of Space-Time, whatever Space-Time turns out to be.

The substance of space is matter, I thought, and matter is made of particles. So if there is such a thing as Space-Time there might be time particles too.

In fact there are such things as time particles. They are called tachyons and they may or may not exist. They are purely theoretical. They only exist in some physicists’ brains. No one has yet managed to catch an actual time particle. They move much too fast. They’ve already slipped into the future before you’ve even begun to let go of the past.

The way this relates to Fred is as follows. Fred is dead. His body is in a box. Even now it is rotting underground, those precious particles of matter coming loose from the organising framework that had previously been his life: his purpose, his substance, those complex, intertwining strings of carbon, all turning to lumpy sludge, his body breaking down into its constituent parts, to slime and rot and organic filth, the flesh sliding from the bones like grease from a warm spoon.

As for Fred, where is he now?

If our bodies are made of particles of matter then maybe our souls are made of particles of time.

So maybe Fred has a new body now, made of time particles. Maybe he’s up and jigging like a ghost on a merry-go-round in his new soul-outfit.

Do you see what I’m doing at this point? I’m wishing Fred a new life.

Here's to your new life Fred, in a body made out of time. Let’s hope you make a better job of it than your last one.

But anyway, enough of his future life. We haven’t finished with his past life yet.

So, now, he’s just been arrested, for being drunk in charge of a motor vehicle: bailed to appear at the magistrate’s in a week’s time, and I’m to be his witness.

He got himself a hotel room and moved into Glastonbury.

Meanwhile, I’ve been charged with keeping my mouth shut about the previous evening’s events, and with finding out whether he really was a paedophile or not.

This was not as far-fetched as it might at first appear. On the one hand, I thought I knew what the explanation for his weird outburst was. On the other: there certainly was something oddly awry about Fred. He had left our little town all those years before, with his new wife and his new child, and his two lively, funny, intelligent daughters, and now, all these years later, I was finding out that some awful things had happened in between. Specifically, one of his daughters had disowned him.

I never did find out exactly how it happened.

He spoke of her in a way that I found very distressing. He used a word that we normally would not even use to refer to our enemies. He called her a c---.

Now I’m no prude. Words are words, and I’m the first to defend the integrity of the English language by allowing all words their right to exist. I love what are commonly known as swear words, knowing them to have a deeply rooted history. In the case of this word, it dates back to at least the eighth century, and was in common usage right up until the 18th century, not as a swear word, but as a proper word for the vagina. It's this association that turns it into a swear word, now considered the worst in the languge. Which tell us a lot about the culture in which we live.So it’s not the word itself that is shocking, but the context. It’s not a word that you would properly use for a daughter.An interesting sideline to this is that it was the word I used to describe Fred, when my son told me he had died. It's not a word I use generally either. But when my son told me he'd heard that Fred had died, and asked how I felt about it, I said, "I don't care. He was a c---."It was obviously associative. It was the word I most associated with Fred. He used it all the time, not only about his estranged daughter, but in front of his other daughter too. And, again, it was hard to understand exactly what was going on here. Was he just being "rebellious", using a taboo word in this shocking way? Or did it indicate something else, some hidden motive?I was shocked, and I'm generally liberal about these things.Why "c---"?

Why had this become his chosen word?

Anyway, back to his eldest daughter, the one who had disowned him.

It seems that she had gone to a prestigious university where she had earned great honours. She was her mother’s daughter. Jealous of her success (or perhaps hoping to emulate her) Fred had himself applied to university and got in. But Fred was not an academic, and he didn’t do too well. He said he thought the lecturers were pretentious twats and he contented himself with scoring with all the young women who were at college with him. Women the same age as his daughters. If this wasn’t child abuse, it was a close-run thing.

That’s something else I haven’t mentioned as yet. Fred took great pride in the fact that he could still score. Ever since he’d left his second wife (or she’d left him, which was more likely the case) he’d made a great show of his ability to pick up women. When you went into a pub with him, within a few minutes he was chatting someone up. The amusing thing for me - as an onlooker - was that he had a stock set of lines that he would trot out as required. After while I could predict his lines even as he was saying them. Each new woman would be subjected to the same set of lines, in almost the same order.

So there was I, usually within hearing distance, smiling wryly to myself, thinking, “you think this is a compliment? You know he says this to all the women don’t you dear?”

It didn’t do well for my view of women and their intelligence to watch them fall for the same set of cliches over and over again.

There was one while he was in Glastonbury: in a pub I took him to. Meanwhile there was another back in Kent, an old friend of mine. So I was caught between all these secrets and suspicions: between my friend in Kent, who Fred was even now betraying and this new woman he was chatting up with right in front of my eyes. Between Morgana and her belief that he was a paedophile, and my challenge, to find out if this was true or not. Between what I knew about Fred and what I didn’t know. Between his crazy, out-of-control behaviour and what remained of an old friendship. Between my thoughts about what might have been happening in his life, and the vague hints and admissions he was sprinkling in my direction. Between my memories of his daughters and their lively conversations and what he was telling me about them now.

One night he offered to put me up in his hotel room, so we could stay after-hours drinking in the hotel bar.

Then his new girlfriend turned up.

We went upstairs and I fell asleep in the spare bed, only to be woken up by the sound of them lovemaking.

I thought, “fuck you Fred. Why do you think I want to hear this?”

When we got up in the morning the room was a shambles.

Fred’s clothes were everywhere. All his stuff scattered about, his pockets emptied in a wide arc, like seeds scattered on the land: money in coins and notes, telephone numbers on scraps of paper, old till receipts, keys, wallet, watch, pens. The beds were a wreck of tangled sheets and blankets. His suitcases had been emptied in knots around the room, just cast around. And all the detritus of his daily life: several day's worth of newspapers, books he was half-reading, washing, towells, soap, all in loose piles. And he'd only been here a day or two.

I thought: “this is what you do to everything in your life. You destroy it all. You turn it all into a horrible mess.”

I think this may have been the moment when he lost my friendship. Somewhere in the night, waking up next to him in this broken down room while he was making love. I got the feeling he was doing it for my benefit. It was some kind of a statement.

But, now, my week in Glastonbury was up, and I was heading off home, back to Kent.

I hadn’t managed to do any work.

Fred decided he was on his way to Kent too, and offered me a lift.

Also he had to go to the magistrate’s to make his plea. Had he pleaded guilty it would have been dealt with there and then.

He was supposed to be going to Cornwall then on to Walsall, and now he was going to Kent instead.

None of it made any sense.

It was symbolic of the state of his life. Shambling around from one place to another with no particular direction, in a state of disorder.

We went to the magistrates where he made a not guilty plea.

His hair was all over the place, his eyes bloodshot, his hands behind his back shaking with alcohol withdrawal.

After that we drove home.

*******