I’ve been looking for a word. It is something like “sacred”. It is the idea of something being set-aside as special, or holy: separated from the everyday world by some particular quality or by mutual agreement. The word could be “sacrament”: the notion of ordinary things acquiring a spiritual significance. Or “sanctification”, the process of becoming holy. But it isn’t quite any of these. The problem with all of these words is their association with religion and with the particular religious quality of holiness, and the word I am looking for does not denote holiness as such. Sometimes, indeed, it can mean its exact opposite.

I’ve been looking for a word. It is something like “sacred”. It is the idea of something being set-aside as special, or holy: separated from the everyday world by some particular quality or by mutual agreement. The word could be “sacrament”: the notion of ordinary things acquiring a spiritual significance. Or “sanctification”, the process of becoming holy. But it isn’t quite any of these. The problem with all of these words is their association with religion and with the particular religious quality of holiness, and the word I am looking for does not denote holiness as such. Sometimes, indeed, it can mean its exact opposite.

Read more here: http://cjstone.hubpages.com/hub/Fellow-Creatures

Read more here: http://cjstone.hubpages.com/hub/Fellow-Creatures

Those of you who know me or who have followed this blog will know that I am obsessed by the Ranters.

They were a sort of anarchist spiritual cult who flourished, briefly, in the period of the interregnum between the end of the English Civil War and the execution of Charles I in 1649, and the restoration of Charles II in 1660: sort of pantheist libertarians, ideological mad men. I keep saying “sort of” because, of course, none of these terms quite fit. They were Christians really, but they took a particularly radical form of Christianity known as antinomianism. “Antinomian” means “against the law”. It refers to the so-called doctrine of free grace, by which it is understood that Jesus came to overthrow the law, to forgive our sins - he died for our sins - and that therefore, we cannot sin any more.

Read more here: http://cjstone.hubpages.com/hub/Fellow-Creatures

It is a Christian thing. It is a Northern thing. It is a pagan thing. It is a Celtic thing. You cannot ignore it. It is in the very air you breath on that day. In the atmosphere. In the psycho-spiritual atmosphere as it were, in the very mind of the people. It is sacred and profane at the same time. Spiritual. Mundane. High. Low. The sacrament of a sanctified meal. Food and drink. A welcome to strangers. The clinking of glasses. A toast raised on high. An offering to the gods. An offering to the sun. A sacred moment in time. A wish. A fulfilment. A hope. A transformation. A resolution.

It is a Christian thing. It is a Northern thing. It is a pagan thing. It is a Celtic thing. You cannot ignore it. It is in the very air you breath on that day. In the atmosphere. In the psycho-spiritual atmosphere as it were, in the very mind of the people. It is sacred and profane at the same time. Spiritual. Mundane. High. Low. The sacrament of a sanctified meal. Food and drink. A welcome to strangers. The clinking of glasses. A toast raised on high. An offering to the gods. An offering to the sun. A sacred moment in time. A wish. A fulfilment. A hope. A transformation. A resolution.

Read more here: http://cjstone.hubpages.com/hub/Fellow-Creatures

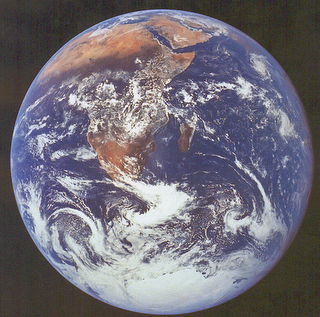

My view of our planet was a glimpse of divinity. -Edgar Mitchell, USA.How big is the Earth? How far away is the Moon? How hot is the Sun?

The answers are as follows:

The Earth is 12,756 kilometres in diameter, or 7,927 miles.

The Moon is 384,000 kilometres from the Earth, or 239,000 miles.

The Sun is 5,777 degrees centigrade at its surface, which is about ten and a half thousand degrees Fahrenheit. That’s quite a suntan. And that is cool compared to the fierce nuclear furnace at its core, which is measured in millions of degrees.

But what does this tell you?

That the Sun is hot, the Earth is big and the Moon is far away.

Does it tell you what it feels like to bask on a warm beach in the sunshine, with a cool drink and your lover there beside you?

Does it say anything about the fairy-tale light of the full Moon caught in the branches of a tree, or what it feels like to hold someone close in the Moon‘s glow when romance is in the air?

Does it tell you anything about love’s mystery or life‘s enchantment?

Does it speak of joy or loss? Does it tell you about grief for a loved-one gone away, or the exhilaration of seeing them again after a period of separation?

And that sparkle in their eye, is that just a reflection of the outer light of the Sun, or does it come from somewhere else: from somewhere deep inside?

Oscar Wilde once said that a cynic is “a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.”

These days we know the measure of everything, and the meaning of nothing.

The question is: is there such a thing as magic any more? Does magic exist?

Not in the measurable world it doesn’t. It has no weight. It has no volume. It has no height. It has no mass. It cannot be detected with scales or thermometers or measuring jars or rulers. You can’t pick it up in your hand and throw it. When it lands on your head it doesn’t leave a bump.

But, then again, neither does love.

If I write down the word “love” what do you see? A few squiggles upon a page. A line, a circle, an angle, a spiral. And in French it is spelt differently again. And in German and Italian and Serbo-Croat. In Chinese it isn’t even recognisable as a word as such. No letters, just a kind of abstract shape in brush-strokes. But we all know what it means.

Scientists might define it in terms of heart-rate and body-chemistry, but they cannot tell you what it feels like. They can attach monitors to your skull to measure your brain-wave patterns, but they cannot tell you what it means to you, nor why every bird in flight, every cloud and every breath of air seems filled with your lover’s presence.

When you are in love your lover is everywhere. The whole world seems to glow with their light. Even the leaves on the trees seem fresh and alive, their delicious rustling like the very message of love.

Because - and this is the truth - love is everywhere. Magic is everywhere. It is a gift from the Earth. It is all around, not as an object, but as a relationship. As a relationship with the Earth.

The Earth isn’t a thing, it is a being. Your relationship to it isn’t one of “I” and “That” - that object over there - it is “I and Thee”, a bonded relationship of mutual recognition and trust.

Without the Earth you would not exist. And without you the Earth would be lonely, I can assure you, for who would be there to recognise her, to see her, to love her and appreciate her, to care for her and to keep her safe from harm?

She’s your Mother, after all. Mother Earth. And the magic is all hers.

I’m not sure what to write about this week. I have two topics on my mind: David Cameron and the newly revitalised Conservative Party and Magners Irish Cider.

I’m not sure what to write about this week. I have two topics on my mind: David Cameron and the newly revitalised Conservative Party and Magners Irish Cider.

I must admit I’ve never tried Magners Irish Cider. I’ve seen a lot of people drinking it down the pub.

You need two hands to drink Magners, since you have to carry both the bottle and the glass at the same time. The glass is full of ice. You pour the cider from the bottle into the glass while trying to look cool. It’s very fashionable right now.

I’ve also seen a lot of well constructed adverts on the TV.

If you notice the emphasis is on naturalness and on the cycle of the seasons. So they bring out a new advert for every season. The current one starts with a flying shot over an orchard with people picking apples, followed by soft-focussed shots of trees and apples blending into soft-focussed shots of fire-places and flickering flames and jolly-looking people sipping cider from clinking glasses full of ice.

“The wonderful thing about this time of year,” says the voiceover, “is that you can always be sure of quite a gathering.”

As it happens I have no need to drink Magners Irish Cider to know what it tastes like. It’s cider. It tastes like cider.

In Ireland it’s not called Magners. It’s called Bulmers. They changed the name so we wouldn’t confuse the two. They share the same name because they are, in fact, pretty much the same.

They are both cider.

Cider is cider is cider.

It’s a traditional alcoholic beverage made from apples. It doesn’t matter what you call it, or what label you put upon it, whether it’s from Ireland or from the West Country or from anywhere else in the entire world. It doesn’t matter whether you pour it over ice or drink it straight from the bottle. It’s cider.

Here in Kent we make Biddenden cider. I’m always surprised that you can’t buy Biddenden's in more pubs since it is, in fact, a very good cider.

And if you like cider, then I would recommend the single varietal ciders they sell in Threshers. Katy is very distinctive and very strong and I’m sure it would taste lovely poured over ice.

The point about Magners is that by adding that all-important word “Irish”, by the addition of a gimmick and a powerful marketing campaign, they have managed to re-brand an old product into something that appears new.

Not unlike David Cameron and the Conservative Party then. Talk about old cider in new bottles.

Magners Irish Cider: time dedicated to you.

David Cameron and the Conservative Party: wealth dedicated to itself.

Some things never change.

I’ve just come back from a holiday in Romania.

I’ve just come back from a holiday in Romania.

I won’t tell you about that here, as I’m saving it for a book.

However, I can tell you about the journey.

I flew from Gatwick to Budapest in Hungary, and caught a coach from there: to Timisoara in western Romania.

A couple of things happened on the journey which told me that I was in for an unusual time.

First was while standing in the check-in queue. You know how it is at airports. They are large and anonymous, full of bustle and noise. The mind becomes abstracted by it all. There are obstacles to be overcome. Hurdles. Queues and queues and queues. You go sort of blank. So you pick your queue, having found your flight number, and then you wait. And wait, and wait. You have to wait because that’s what queues are for. So you wait.

It was only after about fifteen minutes of this blank waiting - watching the people in the other queues either side shuffle forward slowly but surely (there was one bunch of girls off to see a concert, one of whom had on lighted bunny ears and a picture of her idol on her back, and they were all giggling with expectation) - that I suddenly realised that our queue hadn’t moved. Everyone either side had moved up four or five places since I’d joined the queue, while I was still stuck in exactly the same position. Also, the middle aged couple immediately in front of me suddenly seemed noticeably agitated.

I said, “am I imagining things, or is our queue moving more slowly than all the others? I can‘t remember when we last moved.”

“Especially when the check-in girl disappears for about ten minutes,” said the man, visibly stomping from one foot to the other.

“Pardon? Oh yes,” I said. And I looked, and sure enough, we seemed to be missing our check-in person. I couldn’t say whether it was supposed to be a boy or a girl because I hadn’t noticed. I hadn’t noticed because I hadn’t checked because I hadn’t been paying all that much attention. There was simply no one there.

After a while the middle -aged couple realised that their flight was being called, and rushed off in fearful agitation, while I moved up a step or two, and, after a while longer - in which I vaguely contemplated jumping queues - our check-in girl returned, and the queue resumed its steady, incremental, forward-shuffling motion, like beer bottles on a production line, stopping to be filled before rattling on again.

Until I got to the front of the queue that is.

I arrived at the desk, placed my bag on the conveyer belt, smiled as I placed my passport and reference number on top of the desk. It was just a smile, one of those non-committal, half-vacant smiles you give to strangers on whom you are temporarily dependant: like check out girls in supermarkets, or check-in girls in airports. The smile sort of says, “hi, I’m human, I won’t harm you, I’m a nice person, now can you deal with me so I can get on to the next thing?“ As hollow as the spaces in the cavernous hall above. And the check-in girl looked at my face, took in my smile, then promptly burst into tears and went running out the back.

I mean: you just couldn’t make this up.

What can you do? I laughed and looked around. People were looking at me. Everyone had noticed. I shrugged. “Boyfriend trouble?” I suggested, tentatively.

Now what? I was standing there, empty desk in front of me, twiddling my thumbs.

“Um, is she all right?” I said, addressing the girl on the counter next door, after another few minutes of waiting.

“No,” she said. “I’ll be with you in a minute,” she said, and then she, too, disappeared round the back.

At this point my friend in Romania rang to see if I’d checked in all right.

“No,” I said, laughing nervously, “the check in girl took one look at my face and ran away crying.”

“It’s the effect you have on all the girls,” he said.

Eventually the girl from the other counter came back, and got on with the job, typing in my details, asking me about my baggage, putting a sticker onto it before sending it off along the conveyor belt, and I was out of the check-in queue and into the bar for a beer.

Next thing was on the flight.

The air hostesses did all the usual miming stuff: you know, pointing out the escape doors, what to do in the case of an emergency, the life jackets, the oxygen masks and all the rest, while the camp male attendant read out the instructions. He had a very theatrical voice.

When this was over he said: “One person on the flight has a nut allergy. Can I ask everyone on the flight to please refrain from eating nuts.”

Pardon? Was this a joke? One person has a nut allergy, so no one else on the entire flight, even twenty seats away, can open a bag of nuts.

I laughed. Then I realised that no one else was laughing.

I mean: what on earth is happening in this world? Are nuts so dangerous now? Yes, maybe, if you have a nut allergy. Maybe then you shouldn’t eat nuts. But a person sitting fifty feet away: they can’t eat nuts either. Why? In case the person with a nut allergy develops a slight rash and sues the airline I guess.

On the other hand, if nuts are so dangerous it’s a surprise they haven’t banned them from flights altogether. Terrorists could use them. “Watch out, I have a bag of nuts and I’m not afraid to open them!”Well it's no more ludicrous that hijacking a plane using plastic knives and forks, which is what they claimed about the 9/11 conspirators. Or with bottles of water.I was almost inclined to take out the KP nuts I had in my bag and open them anyway, just to watch the reaction. Except when I looked there was a warning on the packet.

“Warning!” it said. “May contain nuts!”

"If the Sun & Moon should doubt,

"If the Sun & Moon should doubt,

They'd immediately go out."

Wm. Blake, Auguries of Innocence (1803).

I've been thinking about my lineage.

Not my genetic lineage, you understand. I'm from Birmingham. There's not many Brummies who can trace their ancestry back that far, having to do with the fact that most people living in Birmingham until the nineteenth century were actually from somewhere else.

No, it's my spiritual lineage I've been thinking about, my political lineage.

Note how those two words run consecutively in my mind. "Political". "Spiritual". To me they are two sides of the same coin.

So I'm on the main shopping street of the little North Kent town where I've made my home these last twenty years - me and a few friends - handing out leaflets calling for an end to the occupation of Iraq, and it's surprising the amount of good will we're receiving. Everyone wants to sign our petition. Everyone wants to talk. Everyone wants to find out what we're doing and why.

I'm engaging people in debate, talking, laughing, sharing jokes and jibes, calling out to people across the street, occasionally arguing, stating the case and the history as clearly as I can: listening, absorbing, paying attention, looking out for the contradictions as people repeat the formulaic mantras of their mutually shared and received world-view.

It's then that I feel it, on the glinting, grey pavement outside Barclay's Bank, one sunny Saturday morning on the High Street. It's like a thread from the past. Down, down it reaches, down. Down through the concrete into the earth below. Down through the centuries, through the ages, through the generations. It's like a life-line, like a conduit, like a deep-seeking tap-root nestling into the rich, dark soil of the English soul: the proud and non-deferential, great historical tradition of radical English dissent.

I say "English" as opposed to "British" or "World" dissent, not because I don't acknowledge the more commonly remembered traditions of Welsh or Scottish or Irish liberation - or African or Asian or Latin American - but just to remind us that the English do, in fact, share these traditions too, in our bearing and in our language.

And I can feel it now, even as I sit at my computer: through the anti-war movement, through the anti-capitalist movement, through Stop the City and Reclaim the Streets, through the poll-tax protests, through the Miner's strike; through Bertrand Russell and EP Thompson and Ban-the-Bomb; through Bruce Kent and Trevor Huddlestone and all the members of the clergy and the laity who have stood up for peace and justice in this world.

On the street, however, it's an older image that comes to mind. I begin to feel like one of those anti-fascist organisers back in the thirties, and I'm reminded of a story an old guy down the Labour Club told me once, of how Moseley and the Blackshirts had arrived in this town, and how the local Fire Brigade had turned out to greet them. Moseley took on his famous heroic stance, chin up, back straight and arm vaingloriously raised, preparing to make his speech. But it was not appreciation that washed over him then. His voice was not drowned out with any kind of applause. Was he a little wet-behind-the-ears? He certainly was. They turned the hoses on him, as he and his fascist henchmen ran dripping from the town!

I guess you can say that all of these illustrations are fundamentally political in nature. True. But who are we to deny the spirit that passes through all of them? And the further back we go, the more clear it becomes just how deeply spiritual it is. Through the Suffragettes, through the Chartists, the urge for democracy is like a cry for human freedom in a world of hide-bound privilege. Through Tom Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft, The Rights of Man and The Vindication of the Rights of Women: these are the radical democratic voices of English dissent as it blazoned into print in the late eighteenth century. Through William Blake (who knew them both) representing the fully evolved, spiritual-political force as it explodes in a blaze of energy and colour, like the rage of eternal humanity upon the ever turning page of history.

And further back again, about a century-and-a-half (as if we needed any more proof) to the roots of all this: to the English Revolution, to Gerrard Winstanley, William Walwyn, John Milton, John Bunyan, the Levellers, the Diggers, the Ranters, the Quakers, to the men and women of this time who were questioning everything, from the right of the clergy to hold control over the bible, to the right of the aristocracy to hold control over property, to the right of men to hold control over women. Or have we forgotten this history already?

And what is it that unites all of these voices, these movements, these peoples, and that makes them, ultimately, spiritual?

It is this: belief. Yes, belief. Because politics requires belief too. Not, maybe, belief in a supreme being, or in gods or goddesses or spirits or extra-terrestrials (these are all optional extras) - or in crystals or aromatherapy or in spiritual healing - but belief in humanity, certainly, and belief in the efficacy of action, and belief in a purpose and a cause in our lives, and, finally, belief in a meaning, because, if it all means nothing, why do anything at all?

And maybe this is the strangest thing of all: that I'm standing on these mundane early twenty-first century streets, with a member of the Socialist Worker's Party, an anarchist, a fundamentalist Christian, and someone who professes no particular philosophy, but who believes in peace and justice; and here we all are, we are all believers.

Belief. Without it nothing would ever change.

He who binds to himself joy

He who binds to himself joy

Doth the winged life destroy;

But he who kisses the joy as it flies

Lives in eternity's sunrise.

Wm. Blake 1793.

You'll have to excuse me this week. This is a very wordy piece. It's all about words. I've been puzzling about us human beings and our relationship to the planet.

It started a few nights back. I have a tendency to insomnia. So it was one of those nights, just sitting there, nothing on the TV, too tired to read, but too agitated in my mind to go to sleep.

I was thinking about our relationship to private property. It's one of the central issues in my philosophy. What do we mean when we say we "own" something? And how does this sense of personal property or belonging relate to our broader sense of being human and to the values we share?

It was that word "belonging" that stopped me short. Think about it. It's a classic Anglo-saxon combination: two words telescoped into one meaning. To "be" and to "long". To be-long.

The word, "long", of course, has several meanings. Principally it represents a measure of extent or duration. Long as opposed to short. A long time as opposed to a short time.

A be-longing is a "being" that "longs" over time, that endures over time. An object or being that "belongs" to us does so by the power of be-longing, of longing over time. Even if it is new, to say that it "belongs" to us is to state our intention to keep it, to hold on to it, to endure with it, to give it time.

But there is another sense of the word "belonging", as when we say that we belong to something or someone outside of ourselves - to a club, to a community, to love, to society at large - when we express our yearning to be a part of something greater than ourselves, not to belong to any particular organisation or thing, but to our shared sense of time and value. When we say we wish to belong.

Whereas the first sense of the word, as an object we own, is exclusive - "that which belongs to you, this which belongs to me" - the second is inclusive: "all which belong together." To belong, in this sense, is to want to share, while at the same time it also means to long for, to yearn for, to desire. To long is to yearn for a long time, longingly - lovingly - with all our hearts. To "be-long" is to endure in this sense of shared longing, with all the people we care about and love.

That dual sense of meaning inherent in one simple word - between the objects we hold exclusively, and the subjects we value inclusively - is what lies at the heart of our human dilemma.

Actually, when I say I started by thinking about property or ownership, that's not quite true. What I started with was the word "common".

It's a very important word in the English language and in English culture. Common as in our House of Commons, who once took the head off a king. Common, as in the Commonwealth, first spoken of during the English Civil War: meant literally, at the time, as the wealth we held in common. Common as in the common people, the commoners, the likes of you and I. Common, as in crude and slightly dirty - which is the sense my mother always uses it to describe people who are too obvious in their feelings. Common as in our common culture, as in the bawdy songs and dances that would accompany us at our festivals, in our feasts of common sharing. Common as in our common law, our common right, our common sense, our common customs and the common lands that once belonged to us all. Common as in community. Common as in communication. Common, dare I say it, as in comrade, the common greeting of friends; as in camaraderie, the pleasure of friends in their mutual company. To commune is to share, both in our worlds and in our needs.

And it is here that we draw a line between our public and our private sense of ourselves, between our public and our private property. We all need both of course. We need our public and our private selves. We need the sense of what belongs to us and our sense of self-belonging. The problem right now is that all the emphasis is on what belongs to us privately, and very little on what belongs to all of us publicly. In fact the very notion of common property is an anathema. We may have a few public services and public spaces left, but either they are already privately owned, or they soon will be. Meanwhile, for those who can afford it - a minority of the world's population - there is a wealth of diversion in the form of gadgetry and personal entertainment to enjoy behind the drawn-out curtains of our own home towns.

All of this - what the merchants of privacy offer to us to consume at our private tables in our private feasts - only serve to communicate our sense of longing in the broader sense of ourselves, our sense of ourselves as communal as well as private beings. In our sense of ourselves as a World Community.

This is the deeply spiritual question that lies at the heart of our hopes for common humanity. How we answer to it will determine the future of life on this planet. Or of human life at least.

Have you noticed how bonfire night has spread itself out over the last few years?When I was a child bonfire night was just that: one night when we would gather in the back garden by a bonfire to watch a few spluttering fireworks before we went to bed. Occasionally we might be taken to an organised bonfire party in some large park somewhere, and watch a spectacular firework display from a roped off space, an agonising distance from the source of heat, while zealous fire-fighters roamed about looking efficient, making sure everything was safe. That was never very much fun, being far too safe (and cold) for any real pleasure.But otherwise this was how it was. Rushing home from school full of excitement and expectation. Baked potatoes. Toffee apples. A box of fireworks that my Dad would ignite with manly glee. Hot chocolate for the kids. Beer for the adults. Sparklers that could write your name in the darkness. A flaming Guy. Sparks that danced like brief angels in the night air. The stinging smell of smoke. Warm woolies, cold noses, and an inability to sleep afterwards as other people's bonfire parties stretched on into the night. And we would watch and listen out of our bedroom window as the screaming surge of rocket-trails became gothic arches supporting the sky.These days it all goes on for weeks. We have become gluttons for our own busy entertainment. It starts several days before Halloween, and ends usually some days after November the 5th.Of course, bonfire night is a specifically English 17th century State-sponsored festival commemorating the victory of the Protestant Parliament against the Catholic opposition. In fact it is the commemoration of a failed act of terrorism, in celebration of which we burn an effigy of a Catholic. It would be like, in the aftermath of 9-11, holding a bonfire party in which we burnt an effigy of a Muslim. Which would be funny, if it wasn’t so plausible these days.

Have you noticed how bonfire night has spread itself out over the last few years?When I was a child bonfire night was just that: one night when we would gather in the back garden by a bonfire to watch a few spluttering fireworks before we went to bed. Occasionally we might be taken to an organised bonfire party in some large park somewhere, and watch a spectacular firework display from a roped off space, an agonising distance from the source of heat, while zealous fire-fighters roamed about looking efficient, making sure everything was safe. That was never very much fun, being far too safe (and cold) for any real pleasure.But otherwise this was how it was. Rushing home from school full of excitement and expectation. Baked potatoes. Toffee apples. A box of fireworks that my Dad would ignite with manly glee. Hot chocolate for the kids. Beer for the adults. Sparklers that could write your name in the darkness. A flaming Guy. Sparks that danced like brief angels in the night air. The stinging smell of smoke. Warm woolies, cold noses, and an inability to sleep afterwards as other people's bonfire parties stretched on into the night. And we would watch and listen out of our bedroom window as the screaming surge of rocket-trails became gothic arches supporting the sky.These days it all goes on for weeks. We have become gluttons for our own busy entertainment. It starts several days before Halloween, and ends usually some days after November the 5th.Of course, bonfire night is a specifically English 17th century State-sponsored festival commemorating the victory of the Protestant Parliament against the Catholic opposition. In fact it is the commemoration of a failed act of terrorism, in celebration of which we burn an effigy of a Catholic. It would be like, in the aftermath of 9-11, holding a bonfire party in which we burnt an effigy of a Muslim. Which would be funny, if it wasn’t so plausible these days.

There are two major November the 5th parties in the UK: one in Lewes in East Sussex, celebrating the victory of parliament in which they have been known to burn an effigy of the Pope; the other, in Bridgewater in Somerset, which marks a day known as “Black Friday”, on the nearest Friday to November the 5th. The story goes that the supporters of the plot had set up beacons across the country which were to be lit if the act was successful. Unfortunately for the people of Bridgewater a nearby beacon was lit accidentally, so they went to bed on the Thursday believing that the plot was a success. It was on the Friday morning that they heard the bad news: hence the name “Black Friday”.The Bridgewater party takes the form of a carnival, which processes though many of the West Country towns in the succeeding weeks.

The word "bonfire" may be a reference to "bone-fires", the burning of animal bones sacrificed to the gods in celebration of the turning seasons. Animal bones are full of fat and would sizzle and crack before they exploded. This would have been the Neolithic equivalent of a firework display, sending dangerous hot sparks high into the night air to mingle with the stars, and bone-shrapnel into the crowds.

Although in England we have moved the date to suit the anti-Catholic propaganda element, it is really an ancient festival recognising the coming of winter. It's historic date is October 31st, All-Hallows Eve, also known as Samhain. Traditionally it is the Celtic New Year, and was always celebrated with fire, with apples, and - possibly, in the dim and distant past – with some form of sacrificial offering. Hence the Guy.It is the night that the dead roam.In Scottish households an extra place would be laid at table to welcome the ancestors. And for all of you who think that Trick or Treat is an American invention: it is not. It's origins lie in the Celtic fringe. People would don disguises so that the visiting dead could mingle freely, and feel welcome in our midst. Who knows whose face it was behind the mask? Was it Uncle George just fooling around? Or Great Uncle Albert, long since deceased, longing to share the warmth of life with the living again?Clearly this is a remnant of that most ancient religion: the cult of the dead, the worship of the ancestors, a religion which still has a huge, if mainly underground, following throughout the world.In Romania, on All Hallows Day, the community gather in the graveyard with candles to celebrate the dead. Prior to that the graves will have been prepared, with fresh flowers and a makeover. On the night there is a hushed atmosphere of reverence, as people quietly commune with the departed, long-gone into the other world. Voices are subdued, candle-flames flicker over faces deep in contemplation, and the atmosphere is electric with expectation, as the quiet ghosts enter the world of the living for a night, and share secret whispers of grief with their loved-ones.

The blazing fire has it's roots in our most ancient form of science too, sympathetic magic: the theory that like creates like. The fire is lit in commemoration of the Sun, whose waning light at this time of year was felt grievously by our ancestors, and it's fierce light was meant to give encouragement to its return. As if the Sun had a personality, and could be appealed to in this way.

Well we can scoff now at such simple notions, while we enjoy the festivals as mere passing entertainment. But it is worth remembering that our ancestors were just as brainy as we are. And while they may not have understood completely the workings of our Universe (how many of us do either?) yet in many ways they had a greater understanding of our place within nature, and a greater respect for the planet on which we enact our petty dramas.Maybe they have something to teach us yet. Who knows?*******

Following is a story I wrote for the Whitstable Times published on the 28th November 2002.

It wasn’t what I was intending. I hadn’t come to this obscure English village to attend a bonfire party. But after a day of panting for breath and sense in a stuffy upstairs room in the Eversley village church hall, listening to a lecture on electro-magnetic therapy and quantum physics, this was where we found ourselves at last: taking the night air, feeding from the crowds, drinking in the atmosphere.

Where’s Eversley you ask? It’s in Hampshire. As for the electro-magnetic therapy and the quantum physics: don’t ask. It makes my head hurt just thinking about those things, let alone sitting in a stuffy lecture theatre hearing about them.

Quantum physics is that branch of science that suggests that the universe is just a pulsating illusion, and that we, as observers, influence what it appears to be. It’s like Buddhism with spirit-levels and particle accelerators.

I said don’t ask.

But back to the bonfire party:

There was me, Stuart, and two of his daughters.

At the time Stuart was in the process of setting up a business to sell the electro-magnetic therapy. I can’t remember the daughters’ names because he has four of them and their names all begin with ‘T’. So it’s Tara, Tasmin, Tori and Teija. Or is that Titania, and Tripe and Toad and Tippex?

Just four fierce, bright girls like jewels, with similar name but with entirely different personalities; and I have two of them sitting at my feet right now, watching as the flames leap and shimmy into the night air, as the smoke swirls and eddies and the sparks rise like doomed fire-flies casting flickering night-time shadows across the expectant faces of the crowd.

There’s something primeval about a bonfire party. It seems to call on something deep and ancient in the human heart. Maybe it’s a racial stirring of some sort: a replay of old dreams from a time before our awakening, a calling of memory.

You think of the huge bone-fires of the ancients, on the nights when the dead walk, when the veil between the worlds is lifted, and the spirits come and join the party.

Or maybe it’s more recent than that: just the memories of childhood and our own modest bonfire parties in the back garden with the family.

Whatever. Bonfire night always seems to set a spark in my imagination.

After that the fireworks start. All those surges of light. The booms, the cracks. The sizzling intensity. The temporary architecture of light in the night sky, like gothic arches etches against the stars. People are oo-ing and ah-ing in the time-honoured tradition.

One of the girls – Tori, is it? Or Toad? – says, “why are people saying that?”

“It’s cos it’s what they’re supposed to do,” says Stuart, with a slightly mocking laugh.

But we all feel it, as our hearts ride up with those rockets, - high, high, higher, right up, right up – as our neck’s strain back, and the fierce light surges and then explodes in an iridescent crackle of intensity. Oo, we think. Ah! And then we laugh at ourselves in a slightly mocking way, knowing we are all the same.

The firework display is spectacular, and worth every penny of the entrance fee. It ends on a crescendo as fifteen rockets mount and then explode all at once in a hail of light like starburst, and then silence as night descends once more, and people begin to make their way home.

Stuart is disappointed. He says, “that should be the beginning, not the end.” And he imagines a place where the drummers are thudding, and where we all spend the night by the fire dancing on our bones and sending our thoughts like fireworks into the sky.

******

Within a couple of days of arriving in the town I went to the Glastonbury Carnival.

Within a couple of days of arriving in the town I went to the Glastonbury Carnival.

Actually it's not really Glastonbury Carnival at all. It starts in nearby Bridgewater around November the 5th, and then worms and snakes and shimmies its way through all the local towns over a succession of weekends. This weekend was Glastonbury's turn.Jude was going to a party. She said, "when you get bored of all the mad drunks you can come up for a few drinks." I never did make it to the party.

I found myself a nice spot, just outside a pub where I knew the barmaid. There was a waste bin, on which I could balance my drink. And then I waited. There were thousands of people about. Many of them had selected their spots hours before. There were deckchairs lined up on the pavement up and down the High St. You could feel the excitement building up in the crowd. Some people were already line-dancing in the street.

I didn't know what to expect. I mean, I'd been given all the statistics. It's the largest illuminated parade in Europe, I was told. Each major float is 100ft long by 11ft wide by 17 and a 1/2ft high, with between 15,000 to 20,000 light bulbs, powered by megawatt generators. I wasn't sure if that was 15,000 to 20,000 light bulbs per float, or 15,000 to 20,000 light bulbs altogether. I tried counting them. I always got lost after about a hundred and fifty.

There were 130 entries this year, including 70 floats. The whole procession is three miles long.

It's all very well being told that sort of thing. But you have to see it to believe it.

I was starting to get nicely drunk by now, waiting for the Carnival to appear. I kept slipping back into the pub for another one. The bar staff were doing a magnificent job. I don't think they had a moment's rest in six or seven hours or more.

While I was waiting I had this monologue going through my head. These are the straights, I was thinking. These are the ones the hippies despise. But who are they? They're everyone. And there's some rogues here and some religious types, and some good people and some bad people and - yes - maybe even a saint or two. And there's clever people and dumb people, and ordinary people and weird people, and - yes - even a wise person or two. And there's sad people and happy people and lonely people and gregarious people. And kind people, and scheming people, and shucktsers and charlatans, and honest people and some who'd sell their own grandmother for a drink. Just like the hippies I'd met, only more of them. It's just the people, that's all, milling about here, there and everywhere, excited, demented, argumentative, rollicking drunk or stoned, getting on with their ordinary lives.

Some bloke slipped in by the waste bin next to me. He was using the waste bin to skin up. He offered me a dab of speed, which I took. Then I bought him a drink, and then he bought me a drink. He was from Essex.

The first figure to come up the road was a man dressed in a hooded cowl with a skull mask dragging a pair of coffins. That's when I knew that this whole thing was pagan. A festival of lights in the dark part of the year. Paganism simply refers to the beliefs and practices of the people. No need for Archdruids or High Priestesses. It's democratic. It has nothing whatsoever to do with religion.

After that it was a brass band, all dressed in Batman costumes. And that's when I started to laugh. It was a bunch of middle-aged men in Batman costumes, with their spectacles stuck on the outside of their masks, deliciously ridiculous. I never stopped laughing after that. And then the floats came. They were, as the statistics had told me, illuminated. But no amount of statistics can describe the effect.

It was like that feeling you had when you were a child and went to your first fair. All the moving lights, the bustle, the rides. The excitement is in the very air around you, like sizzling electricity. It was like the Carnival Floats had got hold of that special kind of spiritual electricity, and that's what they were running on.

They were pulled by giant tractors, with the megawatt generators trailing along behind.

The images were crass: kitsch nonsense. But that didn't matter. It was all the usual stuff: scenes from Star Wars and Disney. The Black-and-White Minstrels. The Telly-Tubbies. There were a couple of Egyptian style floats, with pyramids and hieroglyphs and dog-headed deities. One Chinese float with ideograms. One Japanese, with Samurai. One or two Red Indian scenes, one Christmas scene. I was listing them all as they went by to my friend from Essex. "Look. That's the third Shamanistic float. There's another Egyptian one." But the images didn't matter. The point was, they were fantasies made real.

The people on the floats were either dancing or standing perfectly still, in a frieze. The dancing people looked the happiest.

One float went by and there was an adolescent girl in a skimpy Red Indian costume jiggling about for all she was worth.

My Essex friend said, "look at the tits on that."

"She's not a that," I said. "She's a person."

"Oooo. PC," he said.

But I knew what he meant, nevertheless. My eyes were drawn to her too. And I realised that she loved it, that she was enjoying the attention, and that it was a sexual thing. Sexual but innocent. Sexy. I realised that it was liberating for her. And then I realised it was liberating for everyone else too. It wasn't just girls in skimpy costumes. There were middle aged men and women and adolescent boys, all feeling sexy too, all enjoying the attention, the make-up, the costumes, the lights, living out a fantasy-world before our eyes, gloriously expressive, radiating energy. "It's so human," I kept saying. "It's so liberating."

The Essex bloke had brought his partner over to talk to me. She said, "what path are you on?"

"Pardon?"

"What path?"

"I'm not sure. The footpath, I think. Why? What path are you on?"

"I'm a hedge witch and a pagan Priestess," she said.

The funniest bit came when I found myself dancing to "Ra Ra Rasputin" by Boney M. The float was a frieze of Russian Imperial life before the revolution. Rasputin was being brutally murdered before our very eyes. It was like a still from a bad B-Movie or a scene from a melodrama. I'd been dancing and laughing through the entire procession, jiggling away non-stop. But I was jiggling away even more now, with the sheer absurdity of the moment. No matter how crass the music, no matter how idiotic the floats, it was all so funny. There was a young woman dancing on the pavement in front of me. Everyone was dancing. I said, "you realise what we're dancing to, don't you?"

"Yeah," she said, "Boney M."

"Ra Ra Rasputin, Russia's greatest love-machine," I sang. "Great lyrics."

It was the greatest song in the world at that moment.

*******